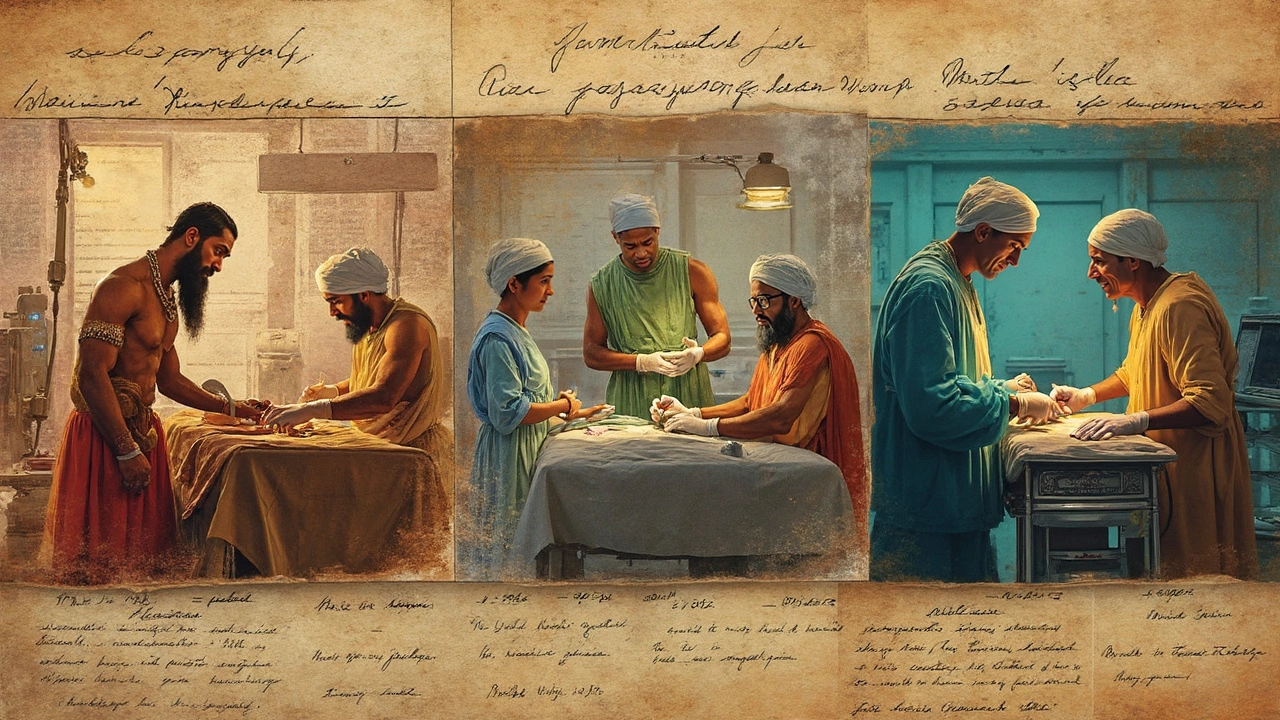

Picture this: a surgeon stands over a writhing patient, armed with nothing but a saw and steady nerves. Anesthesia? Not invented yet. Infection control? Just wishful thinking. Surgeries like these were a roll of the dice, and sometimes, those dice came up deadly. The jaw-dropping truth is, surgery used to be more dangerous than the disease itself. So, which surgery could stake its claim as the deadliest of all? The answer is a wild ride through medical history, packed with outrageous blunders, brave breakthroughs, and human stories that grip you from the very first stitch.

The Grisliest Operation Ever: The Case of Robert Liston’s 300% Mortality

You might think a surgery could only kill the patient on the table, but Scottish surgeon Robert Liston proved otherwise in 1847 London. He was known for being fast—so fast, he could cut off a leg in a matter of seconds, which seemed like a great idea when anesthesia was just a hallucination. But sometimes, speed kills. During one famous operation, Liston tried to amputate a man’s leg in a hurry. In the chaos, he sliced off two fingers of his assistant and nicked the coat of an onlooker, who dropped dead (of shock or fear, depending on who tells the tale). The patient and the assistant later died from infections, while the onlooker’s cause of death still remains legendary gossip. That’s three deaths, one surgery. Medical textbooks call this the only operation with a 300% mortality rate.

The Liston story is often told with a mix of dark humor and astonishment, but it’s a prime example of what happened before surgical best practices. Back then, even a minor operation like a tooth extraction could be fatal, simply because nobody understood germs and hand-washing. This lack of hygiene meant any invasive surgery was, in effect, a deadly lottery.

Why Surgery Was So Deadly: Anesthesia, Infection, and the Unknown

Try to imagine someone cutting into your leg with just a shot of whiskey for pain relief. That was the best-case scenario before ether came onto the scene in the mid-1800s. Before anesthesia, people had to be pinned down by strong assistants during amputations. Every minute the operation lasted, the patient’s odds got worse—shock, blood loss, and agony triggered cardiac arrest as often as the knife did. Surgeons prided themselves on their speed for a reason: the faster, the better, even if it meant shaky hands.

And then came the real killer: infection. Nobody knew why wounds suddenly turned foul, oozed pus, and led to a slow, fiery death. The phrase “hospital gangrene” filled medical texts, but it was just code for deadly, out-of-control infection. Joseph Lister changed the game in the 1860s, making hand-washing and antiseptics standard, but for centuries, the worst killer was invisible. A routine amputation could turn into a death sentence in days—up to 80% of patients died from post-op sepsis at one infamous London hospital, for instance. These weren’t just numbers. Each statistic hides a story of a desperate family, a patient who went under the knife hoping for hope.

The First Open-Heart Surgeries: Risking It All for a Beating Chance

If you think heart surgery is scary today, picture it in the early 20th century, when the odds looked worse than Russian roulette. Hearts couldn’t be stopped safely, and surgeons worked while the heart was still pumping, blood gushing everywhere. The famous case of Dr. Ludwig Rehn in 1896 stands out—he saved a man stabbed in the heart, but this was a rare miracle. Most attempts ended with the chest open, the heart exposed, and a patient who never woke up.

Things changed (very slowly) with the invention of the heart-lung machine in the 1950s. Until then, nobody could reliably operate on the heart. The earliest attempts at repair—like closing a hole or fixing a valve—often caused massive blood clots, fatal infections, or just plain heart failure on the table. The mortality rate for open-heart surgery hovered near 90% for decades. It took generations of trial and error to get that number down. Today, open-heart surgery is one of the most common major operations—with only a 1-2% mortality risk in top hospitals. The stakes were so high in the old days that surgeons used to pray over their scalpels. There’s something kind of heroic about that, even if the outcomes were mostly grim.

Emergency Brain Operations: Last Resorts with Lethal Risks

When people think of tough operations, they often forget the brain. Yet the ancient practice of trepanation—drilling holes in a skull—has been around for thousands of years. Archaeologists have found evidence of this across the world, from Peru to Egypt. In many cases, there’s proof people survived, but survival didn’t mean thriving. Infection, swelling, uncontrollable bleeding—they turned the old emergency brain ops into a deadly gamble. And things weren’t any better in the Middle Ages or even the 19th century, when a head injury would often send a patient down a rapid spiral, no matter how skillful the surgeon.

Modern neurosurgery makes those old cases look like witchcraft. But the risk is still high—even for experienced teams today, brain operations can be deadly, especially in emergencies like a ruptured aneurysm. Back in the days before sterile gloves and high-tech imaging, a tap to the skull was, for most, the end of the story.

Lessons from History: How Surgery (Finally) Got Safer

It’s incredible how fast surgical safety turned around after a few key discoveries. Here’s a handy list of what turned the deadliest surgeries into something you could (almost) bet your life on:

- Anesthesia: Starting with ether and chloroform, these changed surgery from a nightmarish endurance test to something both patient and doctor could actually survive.

- Antiseptics & Hygiene: Lister’s carbolic acid changed everything—suddenly, cleaning hands and tools became the law of the land, slashing infection rates.

- Blood Transfusions: Losing blood used to mean losing your life. Once medics learned how to safely transfuse blood, major blood loss wasn’t always the end.

- Better Tools: Precise scalpels, clamps, and later, operating microscopes gave surgeons control that their wild-eyed forebears never dreamed of.

- Imaging: X-rays, MRI, and CT scans let doctors see what’s going on before they slice in, avoiding deadly surprises.

Today, the deadliest surgery isn't any one operation, but rather a reminder—a warning about what happens when we get too cocky about the limits of knowledge. Even with all our modern miracles, there are procedures so risky that doctors lose sleep over them. The dangers will never drop to zero, but every bloody chapter in the past helped push us a little closer to safe.

No one wants to need surgery. But history’s most dangerous operations—the ones that ended badly, the ones that cost more than anyone bargained for—they’re the reason that, today, you’re unlikely to die from something as basic as a broken leg. Think about that the next time you see a surgeon’s gloved hands. They’re holding not just scalpels, but centuries of stubborn, sometimes deadly, progress.